Tianjin and the Haihe - its ‘Mother River’

A river can make a city, creating an image that will be remembered. A river can also induce a feeling of tranquility. The Haihe, Tianjin’s ‘Sea River’ is one element in many that attracts me regularly back to Tianjin.

Jiefang Bridge near Tianjin Railway Station 2017

Indeed arriving by train from Beijing at the main railway station, my first instinct is usually to walk slowly across its vast exterior concourse to the landscaped river embankments. There I would sit for a while, looking over the waters towards historic Jiefang Bridge. The city feels and looks so different, thanks to the Haihe.

Such positive reactions also derive partly from my Scottish home city, Glasgow, one which has similar characteristics. A former industrial giant bisected by a once busy waterway. There is a saying, “Glasgow made the Clyde but the Clyde made Glasgow.” The close relationship between a city and a stretch of water that was a major factor in facilitating economic and indeed urban growth. The Clyde, once a slow-moving meandering channel flowing from hills south of the city to the sea, to the Atlantic Ocean. The channel was straightened, regularly dredged, allowing ocean-going vessels to penetrate right into the centre of the city. So helping it towards becoming, in the 19th and early 29th century, one of Britain’s leading ports and industrial cities, world renown for shipbuilding. Over time, ocean-going vessels became too large to navigate even through the dredged sections. Glasgow declined as a port but new terminals were built downstream where the river reached the sea. The city’s riverbanks now landscaped, environmentally upgraded and increasingly a place of beauty for people to enjoy.

Tianjin Eye near confluence of Grand Canal and Haihe River 2017

Another similarity with Tianjin, a canal. The Forth and Clyde Canal allowed small boats to connect between west and east sides of Scotland. Before railways opened, cargoes could be moved eastwards from Glasgow to the capital, Edinburgh, via such waterways and the River Forth. Tianjin has similarities. The Haihe connected north and south branches of the Grand Canal with the sea, the Bohai Gulf and via the canal and Tonghui River, with Beijing.

Today, the Haihe is not a river in the ‘true sense’ in that it does not directly rise in the mountains and flow to the sea. However, it is the outlet for several large rivers from a drainage basin of 0.267 million sq.km. whose waters merged into the the Haihe. What we see passing through Tianjin is the final section this vast water catchment area, the Haihe stretching 70 kilometres. It is mostly a straightened, dredged channel starting close to the former Old City of Tianjin. It then moves gently downstream to the ocean where vast container terminals and port facilities stand. Just like Glasgow, the once busy watercourse was rendered quiet over time. In recent years its banks have been landscaped into a very pleasant area for people to once again enjoy the Haihe.

Morning skyline of Tianjin from Shangri-La Hotel 2019

Visitors to Tianjin would comment it is a city seemingly with no hills, although way to the north of downtown there are mountains crowned by the Great Wall. However the urban area is built mainly on flat land only a few metres above water level. The city sits on an extensive, broad plain stretching from the Taihang Mountains to the Bohai Gulf, the latter an extensive maritime gateway to the Pacific. It is interesting to watch construction sites being excavated for tall buildings or infrastructure projects. There is no immediate rocky base or any stony material extracted. Excavations result in vast quantities of brown or reddish sediments and alluvium. Go back 2000 or 3000 years, the coastline was much farther inland than today. What we see as urban was once submerged, it was once underwater. Through geological time, rivers, including the Yellow (Huanghe), have changed course regularly. Their waters, sluggish after descending from the uplands, meandered, flowed slowly while gradually depositing their loads of sediments. This included loess that had originated deep inland, from the ‘Lands of the Yellow Earth,’ Shaanxi. The more deposition, the more courses changed resulting in those sedimentsary deposits drying out. Land emerged from what had once been the sea. The new surfaces, of course, were poorly drained, often marshy.

However, the remaining channels did provide a conduit to the oceans. Over time, small trading communities grew, all interconnected and dependent on water transport. One was the precursor of today’s Tianjin. Earliest traces of settlement are from the Song Dynasty, 960-1126, when a town known as Sanchakou developed on the Haihe’s west bank. This was followed by a larger town, Zhigu, growing on higher ground at the confluence of the Zika and Hai Rivers. It became a transfer and distribution centre for grains and various foodstuffs from central and southern parts of China. Incidentally, the name Zhigu can still be found in modern Tianjin with both a metro station on Line 9 and Zhigu Bridge a couple of kilometres downriver from the Railway Station.

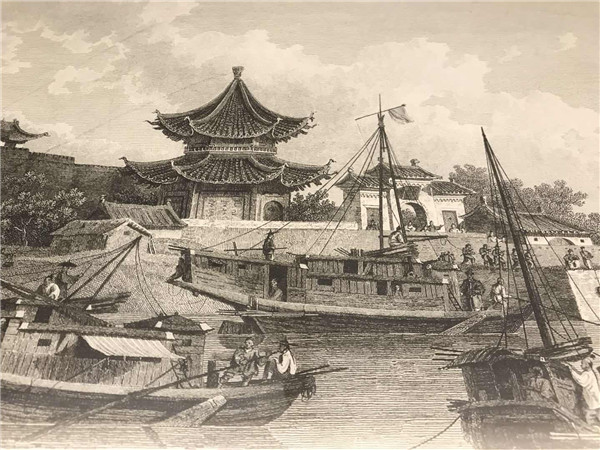

River scene at the historic walled city of Tianjin (Tianjin Museum)

The area benefited greatly by the construction of the Grand Canal which finally connected Beijing 1100 km to Hangzhou between 604 and 609AD during the Sui Dynasty. However it was the Yuan (1206-1368) that the route of the canal became more direct and wider. It would help with carrying essential supplies to Dadu, the ‘Great Capital’, as Beijing was then known.

Zhigu, also called Haijin, saw offices for navigation opened, expanded warehouse and harbour facilities while being a major producer of salt.

Modern Tianjin really developed during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). In1404 surrounded by a rectangular wall it became a garrison town, Tianjinwei or ‘Defence of the Heavenly Ford’. As the main gateway to Beijing, its population grew with many people coming in from Shandong, Jiangsu and even Fujian. By the beginning of the Qing (1644-1911) it had become the leading economic centre of northern China, partly due to its relationship with the canal. By then, the walls reached up to 7.6 metres, enclosing not just bustling living areas but several temples and a large marketing, commercial area.

Today there is a riverside park, almost ‘V’-shaped where the southern Grand Canal (Nan Yunhe) flows into the Haihe and where the northern branch (Bei Yunhe) starts its journey up to Beijing. This was once a really bustling, commercial area with boats loading and unloading in front of the old city walls. Drawings and maps of this can be viewed within contemporary Tianjin Museum. With Tianjin Eye ferris wheel as a backdrop, the canal/river confluence is both a scenic and fascinating part of the city. I have a passion about photography there during winter months when many fishermen sit on small chairs beside holes cut in the ice. Winter temperatures allow for up to three months where the river surface can be frozen. Also there, migratory seagulls congregate. The city is famed as a spot on the bird highway along which gulls head between northeastern Russia, Mongolia and warmer east central China.

Copyright ©

Tianjin Municipal Government. All rights reserved. Presented by China Daily.

京ICP备13028878号-35